The Environmental Protection Agency describes the 2015 coal ash rules as “self-implementing,” meaning utilities had to comply with the rules but the federal government would not oversee or enforce them. Instead, the EPA required utilities to publish the results of their groundwater testing on their websites.

The rules were written that way so that citizens could file lawsuits against utilities for contaminating groundwater or not following the regulations.

And while the rules were very specific in describing which contaminants should be tested and how, the agency was much less specific in describing how that data should be organized and presented to the public. As a result, the information utilities have supplied is difficult to understand and use, undermining the value to the public.

Utilities posted reports that ranged from dozens to thousands of pages. Most included tables detailing the results of their testing (in myriad formats) while others posted the raw lab reports. One utility provided what appear to be scans of paper documents, making it difficult to put the data to any practical use.

For help with the data, we reached out to the Environmental Integrity Project, an environmental group that tracks coal ash contamination at the Ashtracker website. The Environmental Integrity Project shared data for half of the sites in Kentucky and shared expertise on how to best analyze and interpret that data.

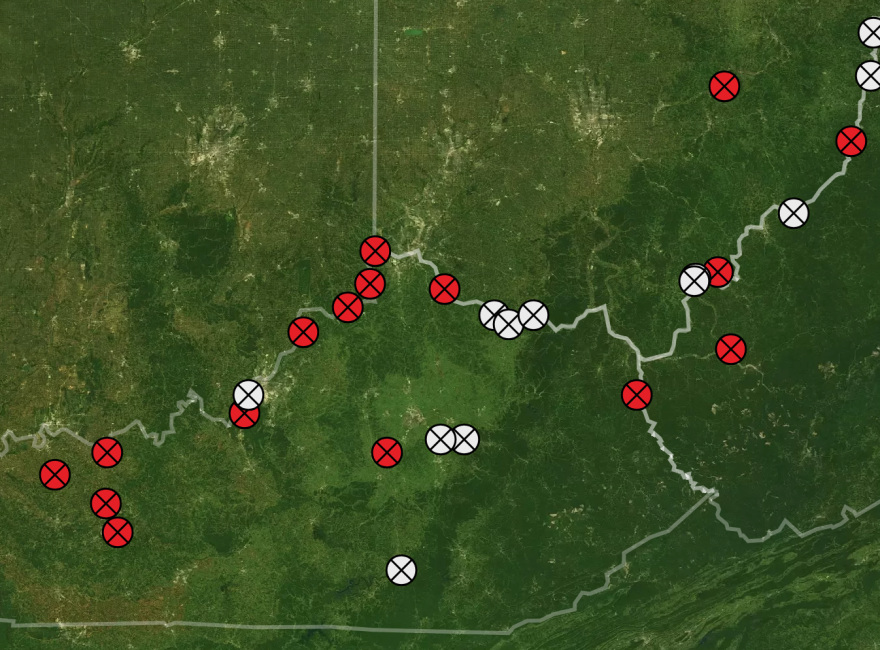

WFPL and the Ohio Valley ReSource collected and analyzed groundwater monitoring reports for most power plants with coal ash waste sites covered under the EPA rules in Kentucky and West Virginia.

For each site, we averaged groundwater samples and compared them to background levels. This is a simplification of the complex statistical analysis used by utility companies.

How we did it

The data tables released by many stations did not allow an easy look at a single well’s water samples over time. Each page would represent a sample date, each column a different well, each row a different contaminant.

Some data were structured like this:

And others, like this:

In order to create a look at a single well’s contaminant levels over time, we had to take all of that data and put it into a structure that looked something like this:

Where each row represents a single well, on a single sample date, for a single contaminant.

Each station tests two types of wells: upgradient, or background wells and downgradient wells. Upgradient and background wells are like the control sample in an experiment. They are installed at a spot where the groundwater has yet to reach the coal ash impoundments or landfills. Downgradient wells are installed in areas where the groundwater has passed under the coal ash.

If samples in both the upgradient and downgradient wells are high, it is possible that the site being monitored was not the cause of the contamination.

Roadblocks

It was challenging and time consuming to get the data from the reports into the format we needed to make this analysis possible. We used a variety of tools, such as Tabula, a program that turns pdf data into spreadsheet data; python and R, programming languages that helped us structure the data; and Excel, a spreadsheet manager.

However, for certain sites, like Little Blue Run which lies on the border between Pennsylvania and West Virginia, none of those tools helped.

Little Blue Run, a FirstEnergy station, uploaded image-based reports to the EPA. Next time you open a pdf file on your computer, try to select the words on the page. If you can, your document is a digital pdf. If you can’t, your document is an image-based pdf.

Image-based pdfs are amazingly difficult to turn into spreadsheet data. You need to use an optical character recognition (OCR) program to turn the images into the text that they represent. These OCR programs frequently misplace commas and periods. They turn 0’s into 9’s. Which is a big problem when you’re looking for precise information about arsenic or radium contamination levels.